Salt & the Sovereign

Salt & the Sovereign

Couldn't load pickup availability

Narrated by Marni Penning. Listen to a sample:

- Purchase audiobook instantly.

- Receive download link via email.

- Send to preferred listening device and enjoy!

5x8 paperback

- Purchase paperback.

- Your order is printed in the UK and shipped within 5 business days.

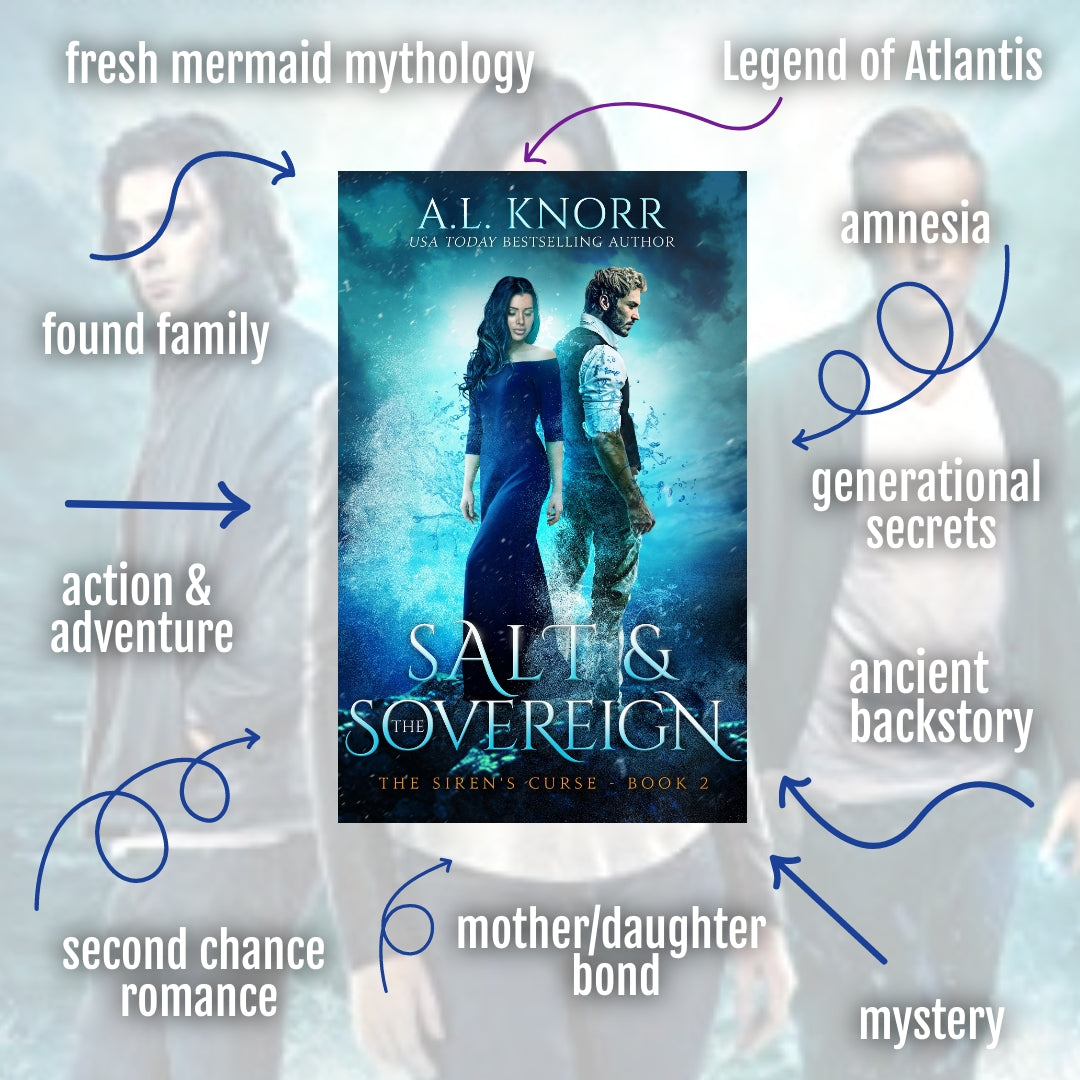

tropes 'n details

- mermaids

- sweet romance

- action & adventure

- Legend of Atlantis & Okeanos

- set in Poland, Canada & N. Africa

- full novel

- sequel to Mermaid's Return & Born of Water

- completed trilogy

- gift with purchase of the audiobook

Synopsis

Synopsis

Deep in the ocean, a rivalry rages. Can one siren’s song turn the tides of hatred?

After witnessing senseless murder, Bel vows to end her mother’s tyrannical reign. But as a young mermaid, she has no choice but to spend multiple mating cycles on dry land before she can qualify for the crown. As she strives to capture a man's heart, the underwater realm flows with the blood of the queen's enemies…

Every moment wrapped in the strong arms of her human mate, Bel risks the madness of the siren's curse. And if she doesn't return to the sea soon, she'll lose her memories and her chance to cure the centuries-old feud. If fixing the deadly conflict is even possible…

Can Bel claim the throne before her mind and the kingdom fall to ruin?

Salt & the Sovereign is the captivating second book in The Siren’s Curse YA fantasy series. If you like ancient mythology, plucky heroines, and deep-water rivalries, then you’ll love USA Today Bestseller A.L. Knorr’s seafaring adventure.

Intro to Chapter One

Intro to Chapter One

Everyone called my mother Polly. It was a name for sweet young girls, kind old ladies with knitting nestled on their laps, or clever feathered pets from tropical countries. I remembered thinking from a very young age how much the name did not suit the imposing character and visage of Polly Grant.

At six feet tall and with eyes so dark they appeared black, my mother was difficult to miss in a crowd. When she spoke, her words came out with an authority that convinced all those within hearing range that she was a woman not to be tested. She wore her long, dark hair in a high circular braid like a crown, which only added to her air of austere royalty.

I was five. Looking up at my mother was like looking up at a giant. Standing on the platform at a train station in London, she did not hold my hand, but instead rested her own heavy one on my shoulder. She was gazing off to the left, still as stone, her dark eyes trained on the tracks in the direction our train would arrive from. Her hand seemed to grow heavier by the moment. The suffocating weight and the heat of it made me feel like I was being slowly crushed into the earth. I wanted to push her hand off and take a deep breath, but I dared not. Polly was swift to quell rebellious behavior.

A short, elderly man in a black bowler stood a few feet away and to the right of me. Holding a newspaper in his hands, his face was not visible behind the pages. I could only see the gray tufts of hair curling out from under the brim of his hat. I stared at him, waiting for him to move the newspaper so I could see what he looked like. Waiting for trains was boring.

Sending my right foot out to the side, I slowly moved away from my mother, just enough to begin to slide out from under her oppressive grasp.

“Do not wander, Bel,” she said quietly, not looking down at me. But she dropped her hand, and that was all I wanted. I took a deep inhale, relieved.

“No, Mama.” Reaching into the pocket of my wool coat, I pulled out a piece of crinkled paper. “Just putting this wrapper in the bin.”

She cast me a brief glance but didn’t reply, and returned to her sentinel stance. I had learned to keep little bits of trash in my pocket for just this reason––small planned escapes of the kind only children reveled in.

Stepping back and turning, I scanned the station for a garbage receptacle. There were only a few passengers on the platform because it was just after lunch on a week day. I spotted the bin and made my way over, walking slowly and quietly, because only unruly and disobedient children ran and screamed on train platforms and on roads and in the parks.

Savoring my bit of freedom, I tossed the wrapper and watched it fall. When I returned to the platform, I made sure Polly could see where I was, but I didn’t return to her right away. I stood to the side a little, watching the old man reading the paper.

Some sixth sense told him he was being watched. His gaze finally dropped to the little girl in the blue woolen coat––me. I was impressed with his thick white moustache. The moustache was curled up at the ends, like a small set of horns. We made eye contact. His moustache lifted and his pink cheeks rounded. The corners of his eyes crinkled.

I smiled too, drawn to his sparkling eyes and kind expression. The full-grown human male was captivating to me, since I’d interacted with so few of them. Not very many people looked at me the way he was looking at me––like he really saw me. Polly drew all attention to herself, and I didn’t mind. Sometimes I felt like a small insect flying low to the ground, busy and invisible.

The old man glanced at my mother and back at me. “You must have gotten your eyes from your father,” he said. “So blue. Like the sky, or a tropical sea.”

I didn’t know what to say to this. My father was not a part of my life and I had no memories of him. I knew other children had fathers, of course, but Polly was enough parent to fulfill the role of both, as she liked to remind me. I had never questioned the source of my eye color before that moment. The idea of getting some feature of mine from my father had never occurred to me. It was true, my eyes were very different from my mother’s. We had the same dark hair, the same white skin, and we were both slender, but her eyes were dark and round, while mine were bright and tilted up a little at the outer corners. That my eyes were different from my mother’s had never before been pointed out to me, and it was a moment that changed something. It was a moment of growing up, of questioning, of realization. One’s features were inherited, not given as if by magic, but bequeathed.

“Where are you going?” the kind man asked, and I liked his voice. It was gentle and soft, and he asked me this question as though he knew that if he said it too loudly it would alert Polly and our interaction would be over.

“To the seaside,” I said, just as quietly. “Where are you going?”

“Bel,” my mother said sharply, looking over. She snapped her gloved fingers and pointed at the ground beside her.