Sins of the Fallen

Sins of the Fallen

Couldn't load pickup availability

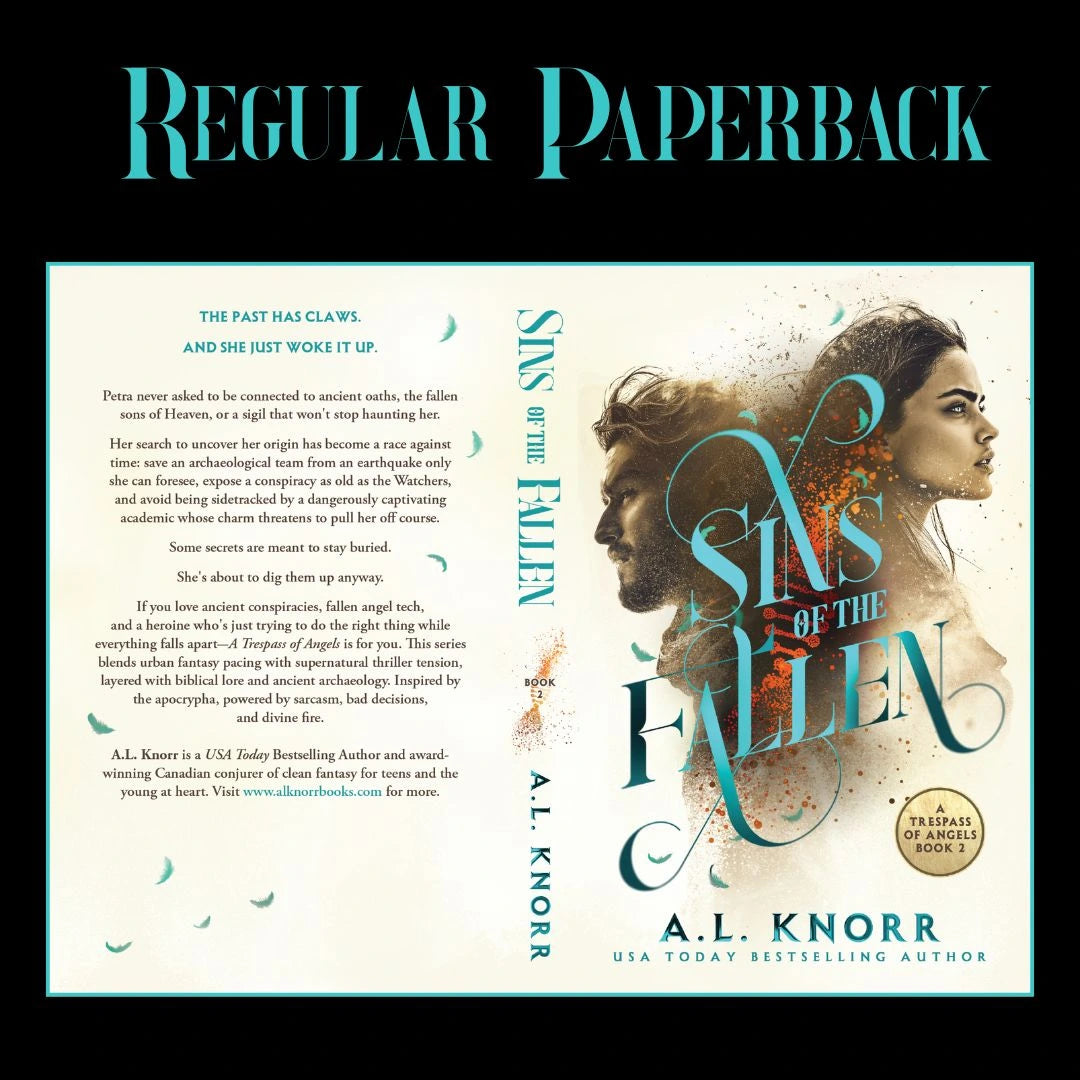

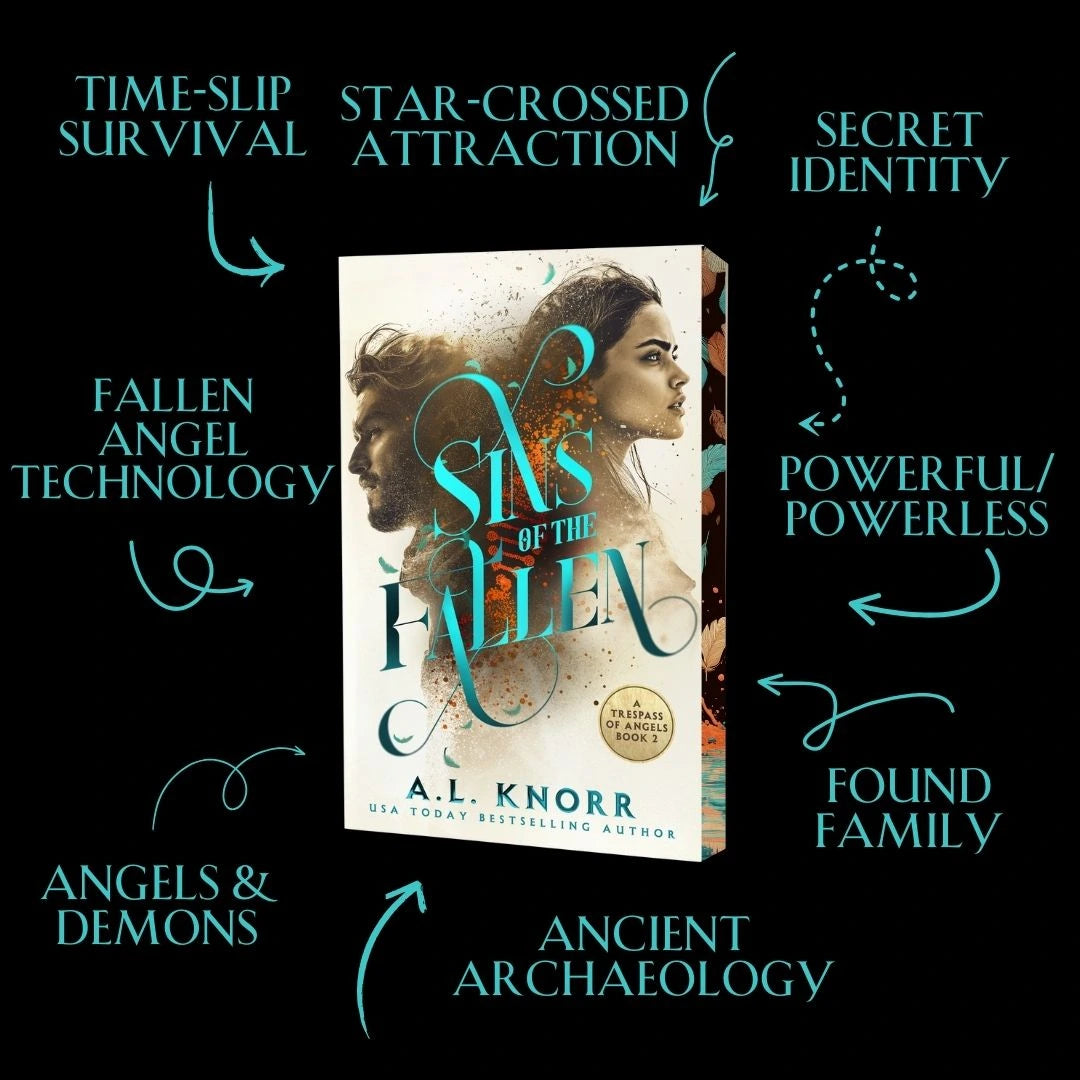

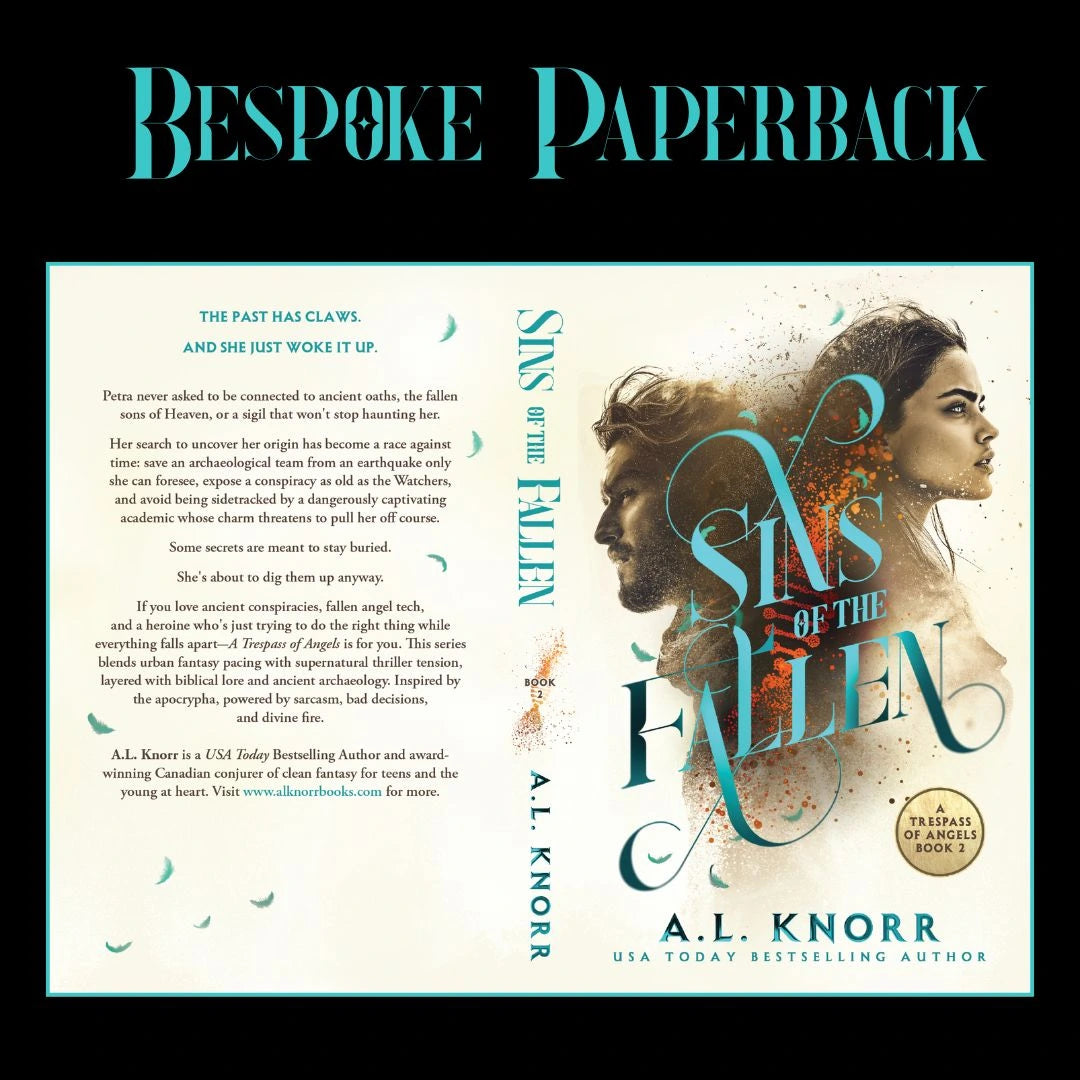

The past has claws. And she just woke it up.

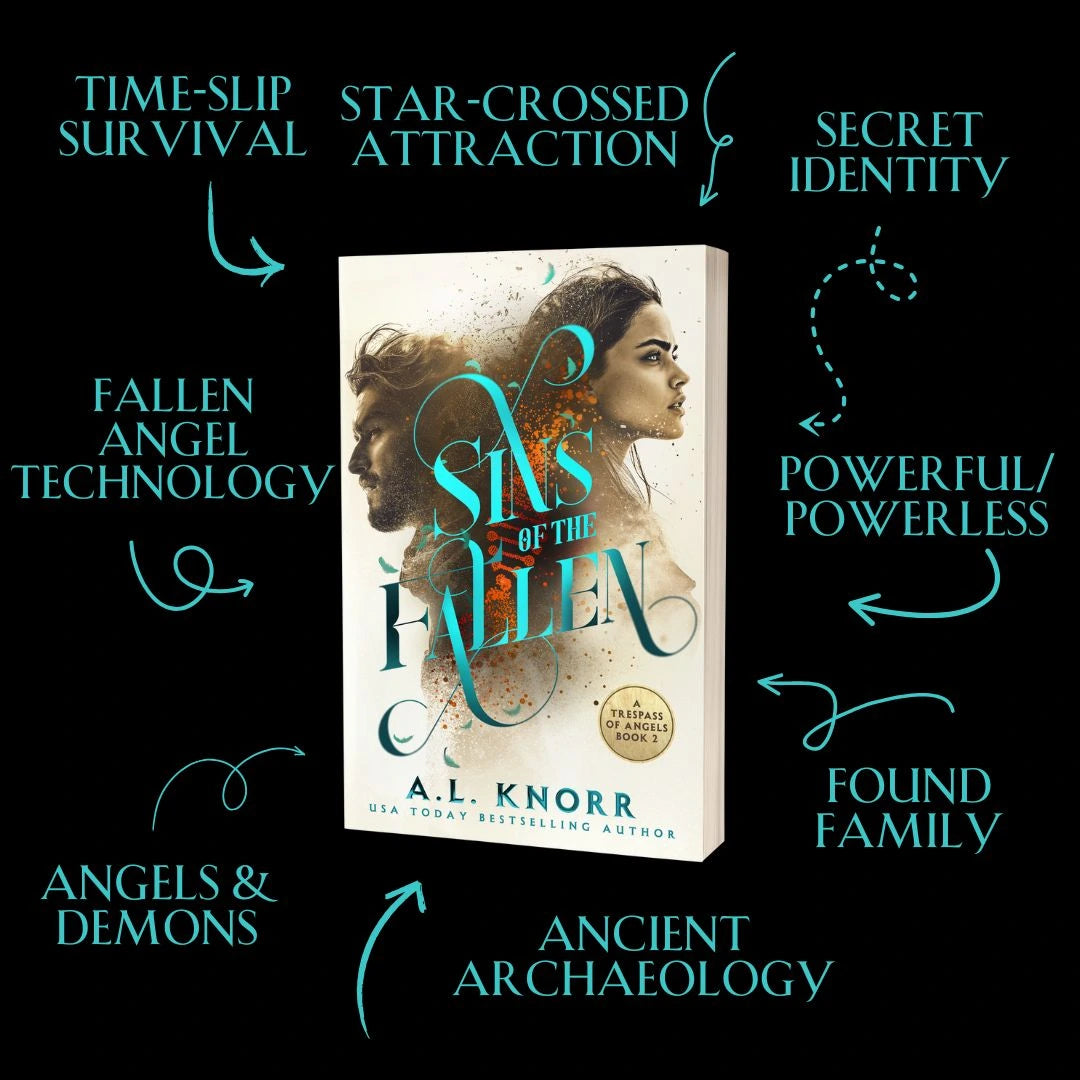

Petra never asked to be connected to ancient oaths, the fallen sons of Heaven, or a sigil that won't stop haunting her.

Her search to uncover her origin has become a race against time: save an archaeological team from an earthquake only she can foresee, expose a conspiracy as old as the Watchers, and avoid being sidetracked by a dangerously captivating academic whose charm threatens to pull her off course.

Some secrets are meant to stay buried.

She’s about to dig them up anyway.

If you love ancient conspiracies, fallen angel tech, and a heroine who’s just trying to do the right thing while everything falls apart—A Trespass of Angels is for you. This series blends urban fantasy pacing with supernatural thriller tension, layered with biblical lore, elemental magic, and one very loyal hacker who refuses to quit. Inspired by the apocrypha, powered by sarcasm, bad decisions, and divine fire. Perfect for fans of Cassandra Clare, Marie Lu, and readers who like their romance clean but their stakes cosmic. Start with Born of Air, then dive into Shadows of the Fallen.

The Bespoke Paperback Features:

- ⚡ High-Gloss Finish

- ⚡ Beautiful color character art

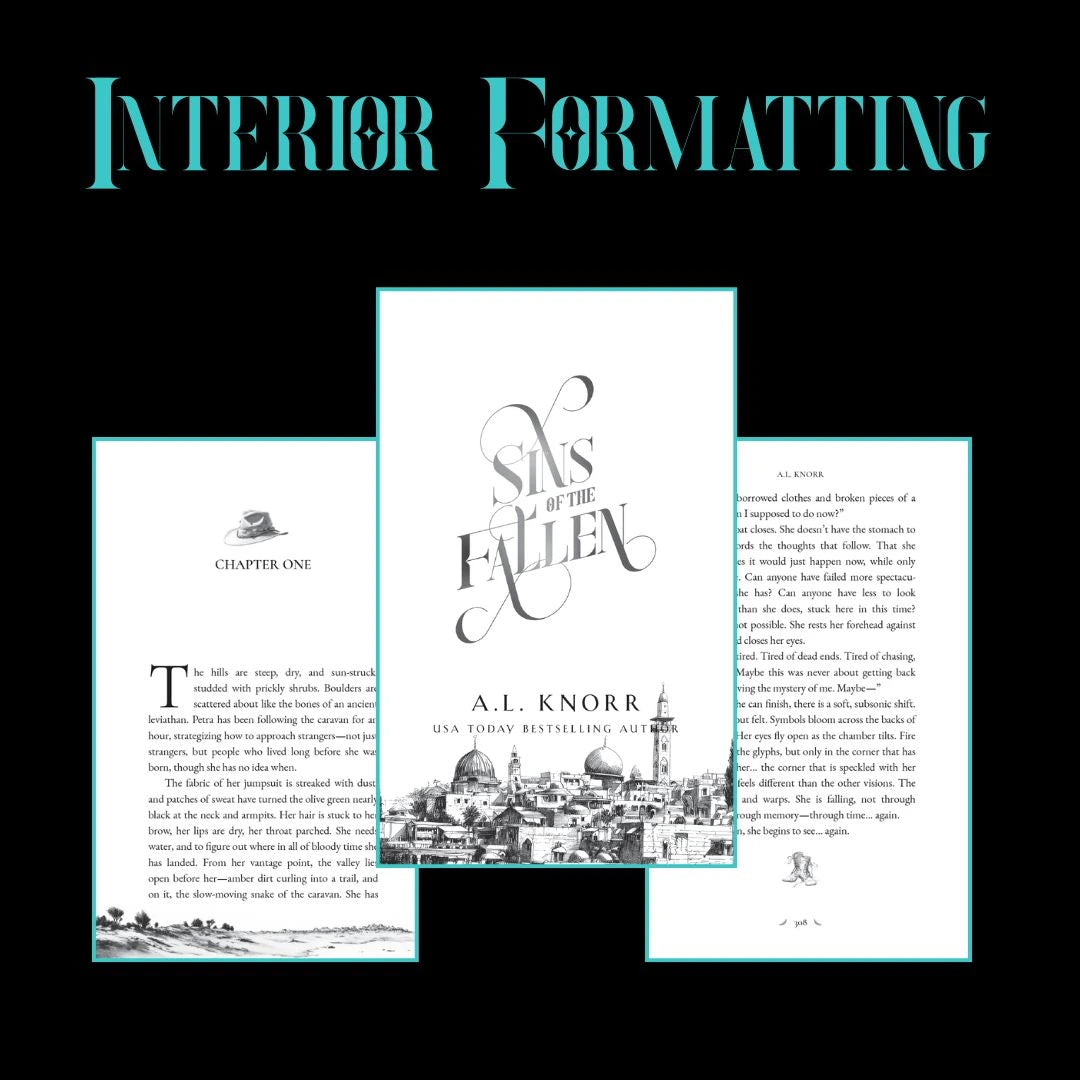

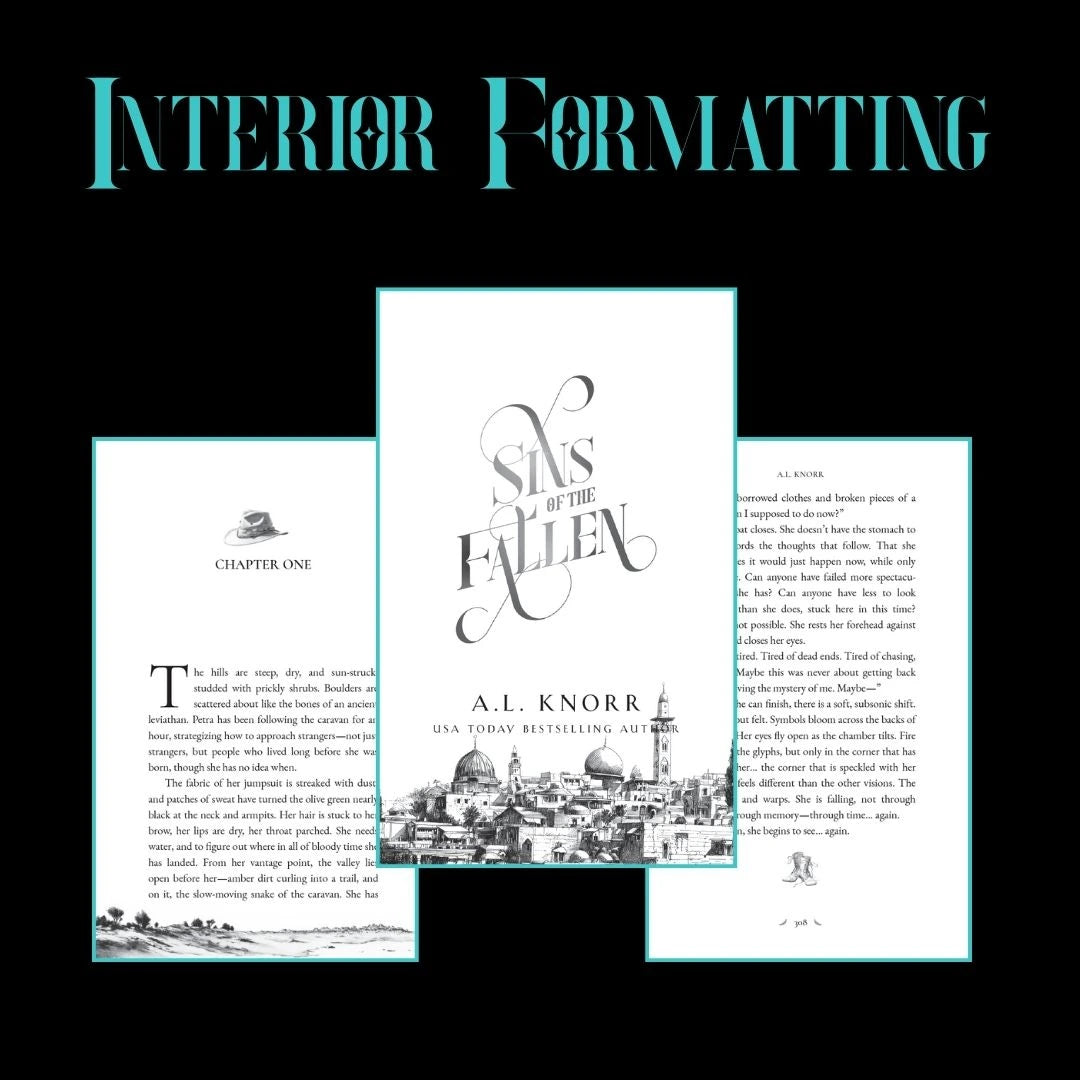

- ⚡ Custom interior formatting

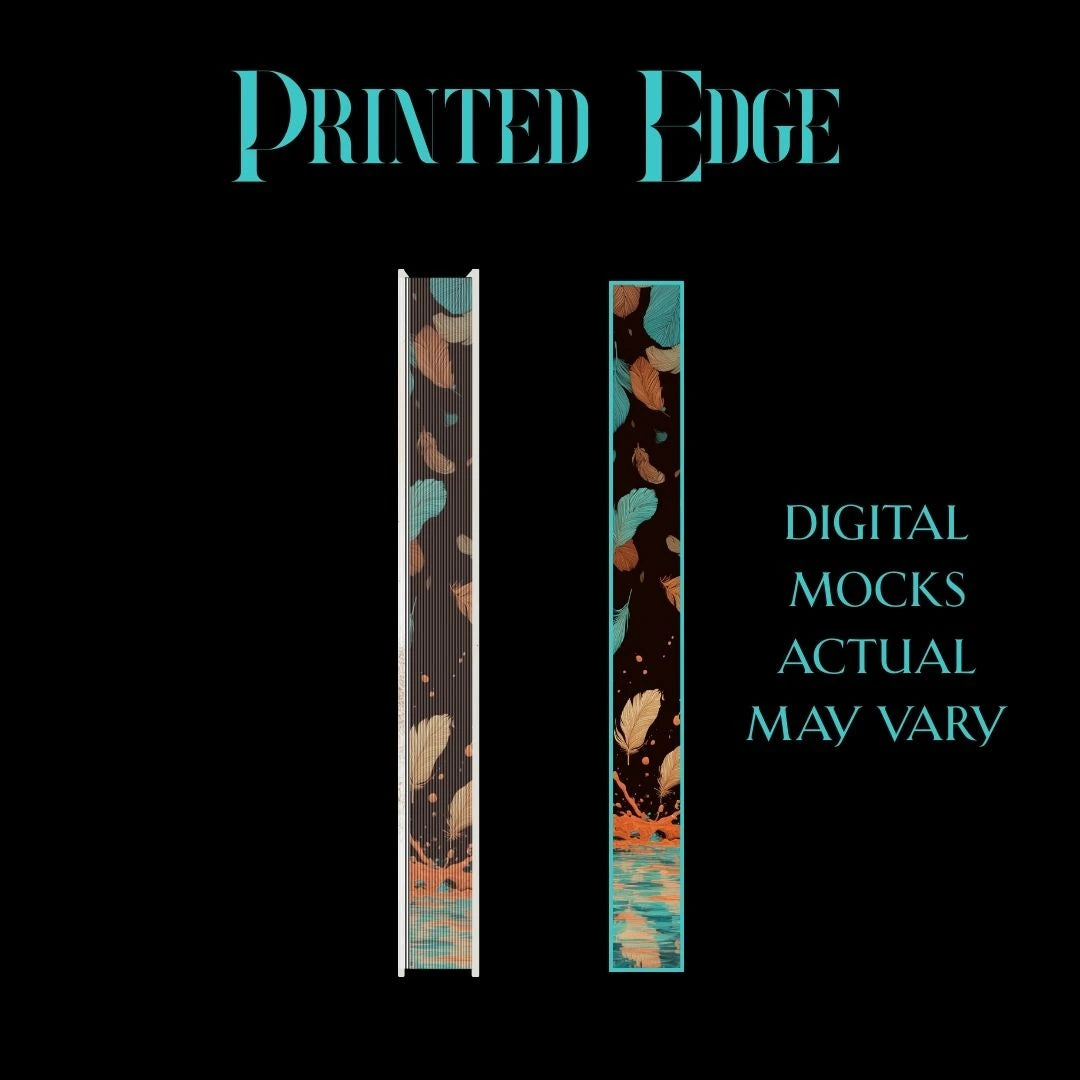

- ⚡ Printed edges with 'falling feathers reflection'

The Regular Paperback Features:

- ⚡ High-Gloss Finish

- ⚡ Custom interior formatting

Read an Excerpt

Read an Excerpt

The hills are steep, dry, and sun-struck, studded with prickly shrubs. Boulders are scattered about like the bones of an ancient leviathan. Petra has been following the caravan for an hour, strategizing how to approach strangers—not just strangers, but people who lived long before she was born, though she has no idea when.

The fabric of her jumpsuit is streaked with dust, and patches of sweat have turned the olive green nearly black at the neck and armpits. Her hair is stuck to her brow, her lips are dry, her throat parched. She needs water, and to figure out where in all of bloody time she has landed. From her vantage point, the valley lies open before her—amber dirt curling into a trail, and on it, the slow-moving snake of the caravan. She has counted at least thirty people, eight wagons and ten pack animals. The sound of hooves and bells drift up to her, softened by heat shimmer. A child cries. It’s a family group, or a group of families, seeing how the male figures aren’t dressed like they’re all from the same class. She’s studied their rhythm—a pulse of motion, then a pause as someone adjusts a strap, looses the load from a donkey, or dismounts to offer a ride to a weary companion. A boy chases a chicken that must have escaped from a wagon.

Petra has been keeping above them, downwind, waiting for an opportunity—and for her nerve to kick in. What are the odds that one of them speaks English? She has a smattering of Arabic, a little French, but is nowhere near fluent in either language.

A change whispers over the caravan, subtle, as the lead riders gesture to the ones behind and a murmur of conversation drifts up to Petra. Then she sees the reason for the shift in energy: a cluster of date palms circling a stone cistern. The trees offer a strip of shade. The caravan fans outward, a flock breaking formation. If she’s not mistaken, there are a few groans of relief from the animals.

Now is her moment. She needs to approach them at the watering hole, when burdens are lifted, tempers cooled and thirst slaked. She wipes her palms on her thighs and moves through the brush. Look thirsty Pet, not dangerous. Hands out, show them you’re unarmed. You’ve seen Lawrence of Arabia three times. No sudden moves. Don’t be stupid. Don’t be proud, and you might get a drink and some information. Make eye contact, but look meek and gentle, and a little desperate… that won’t be hard.

She wishes she had different clothes. Her jumpsuit is a neon sign that screams oddity, stitched by a god with a dry sense of humor. A hair covering would help, and shoes that are not so obviously shiny and white under all the dust. She considers taking off her sneakers and hiding them inside her jumpsuit, but the rocks are sharp, and a suspicious bulge would probably be more dangerous than the shoes. She descends, slowly, sidestepping over the steeper bits. Every few steps she pauses to observe the group. They’re still unaware of her.

A man wrapped in a faded keffiyeh and a dust-colored burnous crouches near the edge of the palm shade, his back against a tree and his rifle across his knees. His skin is dark, sun-scoured; his mouth a hard line. When he sees Petra, he stands quickly, hands gripping his rifle. She’s thankful he keeps the barrel pointed toward the sand. Children squeal next, and a woman by the cistern drops her water jug in surprise.

“Wahad! Shufuha!” one of the children screams.

Arabic then.

“Salaam,” Petra calls, lifting her hands a little, palms out, as she asks for water. “Ana… urged man’ … min fadlikum.”

More adults approach the cistern, putting the children behind them, though small faces peek between legs and around hips. There are bursts of Arabic from the group. A woman in an indigo abaya approaches, square-hipped, short and very sturdy. Her robe is dusty, but her scarf is tight and spotless, wrapped like a crown around her head. She reaches boldly for Petra’s sleeve, rubbing it between thumb and forefinger as though to convince herself that Petra is real, and so is the sturdy fabric she wears. The jumpsuit is stiff, the texture, stitchwork, the strange gleam of synthetic thread—it’s apparent from her expression that the outfit makes no sense to her. The woman’s eyes—dark as dried figs, sharp and observant, and colder than Petra would like, missing nothing—drop to her sneakers and widen a fraction, then whip back to her face, laden with suspicion.

“Ayn zawjuki? Ayn waliyuki?”

Another woman approaches, this one is older, her spine as curved as a question mark, her face seamed with age. Her gaze is kind, pitying. Soft, parchment hands offer a ladle filled with water. Petra reaches for it.

“Shukran,” she whispers.

But as Petra’s fingers brush the handle, the woman in the indigo robe knocks away the ladle. The water splashes onto the older woman and into the dust with a hiss. The older woman tsks in disgust at the indigo lady, and a high-pitched argument ensues. The crowd presses in. Petra’s throat closes as anxiety and discontent move across their faces. She takes a step back, then another.

A command cracks across the small oasis like a whip. “Ruhū ’an tariqihā. Kara!”

The women cease arguing and the crowd parts just enough for a man to push his way through; his brow is furrowed, his sleeves rolled up, and a dark smudge of oil crosses one arm. His voice is stern, his Arabic slower than theirs, as he clearly addresses the woman and the crowd, not Petra. “Hadhi al-mar’a ma’ī. Tatrukūhā.”

Doubt seeps in, voices falter. Some move away to resume their own business. A few watch Petra a little longer as the man approaches her, speaking softly in English.

“You’ve made quite an impression,” he says in a distinctly British accent. “Here.” He hands her a waterskin, which she takes with a grateful sigh.

“Thank you.”

The relief from the warm water she squeezes into her mouth is as precious as diamonds. She feels the man studying her as she drinks, taking in her clothing, her naked hair, her shoes. When she hands back the skin, he fastens it to his belt without taking his eyes from her.

“Walk with me.” He turns away from the well and Petra follows, nearly tripping over a small girl with a dirty face staring up at her in open curiosity.

“Ahlaan,” Petra says gently, greeting the child.

In answer, the little girl lifts her hand and shows a fig she is holding. It is bruised and worse-for-wear, but it’s food. Petra’s mouth waters, but even more impactfully, the girl reminds her of Maria, and for a moment her heart aches. Then the girl shoves the fruit into Petra’s hand and scampers away, giggling.

The man hasn’t slowed down, so Petra jogs to catch up to him, smiling as she takes a bite of the fig. Sweetness explodes across her tongue, and it is amazing what the flavor does to lift her hopes. Maybe, just maybe, she won’t die here in the desert, as dried out as that mummy she unearthed in the Sahara.

The man leads her to a wagon; the nicest one in the caravan, Petra notes. As she swallows the last of the fig and they step into the shade, she studies her savior for the first time. He’s a man made of angles: tall but not imposing, lean and long-limbed, like he never quite finished filling out his frame. His nose, forearms, and the backs of his hands are sunburned. He has pink-toned skin, rather than the olive-tone of the rest of the caravan. Petra suspects that sunburned is his daily state of life. His laugh lines look carved into his skin, the result of years of squinting into the Levantine sun. His face is narrow and sharp, with a blade-straight nose and cheekbones that make him look stern, although his blue-gray eyes are kind. He has a reddish beard, neatly trimmed, and when he takes off his hat to wipe his brow, she sees that his hair is dark blond with a hint of copper, sun-bleached and flattened to his skull.

He opens a trunk sitting at the back of his wagon. Gears and tools are strung from hooks along the inner wall of his wagon, which explains the smells of metal, cedar shavings, and faint traces of oil. A half-dismantled oil lamp sits on a tarp. He rifles through his trunk and pulls out a small wooden box with a metal clasp. Inside it are folded bits of fabric that he rifles through before pulling out a swatch of something thin and gunmetal gray. He hands it to her.

“You’d better cover your hair. They think you’re a jinn.” His lips twitch. “Or worse, a tax collector.”

Petra thanks him—torn between laughter and tears at being pegged as a demon—and loosely swathes her head in the fabric, tossing the end over one shoulder like a forties movie star. She has no idea how to tie it the way the other ladies do.

“You’re a mechanic.” She gestures to the equipment. “What do you fix?”

“Mostly engines, but really, anything and everything. Why do you think I stepped in on your behalf?” He looks at her feet, the zipper on her jumpsuit. “You’re not from here, that’s obvious. You speak English, but you don’t sound British, yet not quite American either.”

He waits a beat for Petra to fill in the details.

She takes a breath, her mind racing, and decides to stick as close to the truth as she reasonably can. “I’m… Canadian.”

She can tell by his expression that he’s heard of it. So… she is post-1867 Dominion formation, that’s one clue. How else can she learn what year it is without alarming him?

“What is your name?”

“You first,” he replies with a half-smile, his gentle gaze probing.

“I’m Annie,” she says softly, making a calculated decision to extend her hand, something that was probably not done in this time—whenever this is—but how he responds will tell her about him. She wishes she could read his mind. She needs an ally, and maybe he could be that for her.

He looks at her outstretched hand for a beat too long. His expression says that he is trying to figure out whether making physical contact with her is foolish or necessary. She likes that he doesn’t glance around to see who is watching; he is a man who doesn’t overly care what others think. That could be helpful. Still, while his eyes are not hostile, neither are they trusting. He seems more curious than anything else. When he takes her hand, she allows a relieved smile to cross her face.

“William Johann Meiers.” He releases her hand quickly after a single pump with dry, calloused fingers. Pulling a crate out of the back of the wagon, he sets it on the ground. “I go by Johann, here. Sit, Annie.”

There’s a buzz of voices at the well, casual talk, relaxed sounding. Petra gets the odd glance, but the caravan is back to the business of everyday life. The canvas door over the rear of Johann’s wagon flaps in a gentle breeze as he pulls out another crate and a lumpy fabric sack. He sits down beside her then opens the sack and offers her the dates that are inside.

He finally asks what surely has been his most burning question: “What are you doing out here in the wilderness?”

Petra takes a bite of the date, chewing slowly to give herself time to think. It’s better if she presents herself as an orphan—which is also true to life—but still someone with family, so she is less vulnerable.

“I came east with my… uncle,” she says, inventing as she goes. “He’s”—she exhales, letting a tremor enter her voice—“an archaeologist. Holy sites. There were some… dangerous nomads. We became separated, and unfortunately, I got lost.” She puts a hitch in her throat on the final words, and covers her mouth with her hand, leaving her story there. Let him assume she’s an emotional female, then maybe he’ll be too polite to pry but empathetic enough to help.

Johann weighs her words, looking as though he’s not sure he should believe her. “You don’t speak Arabic well.”

“That’s true.” She gives a regretful sigh. “I’ve only studied phrases. I was never meant to be anywhere on my own.”

“Yet, here you are. On foot. No caravan, no guide, no proper clothing. Not even any water skin. You have no idea which direction your party might have gone?”

She shakes her head. “I’ve gotten utterly turned around, I’m afraid.”

For a moment, silence stretches between them. He shifts, his eyes narrowing on her getup again. “What are you wearing?”

“Oh.” Petra looks down at herself as though it never occurred to her that someone might find her clothing strange. “My uncle had these shoes and suit made for me. He has some odd, though practical, ideas and he never cared for propriety. These are easier for traveling, easier to clean, easier to attend to my dig duties in than a robe or dress. The shoes were made in Canada. They are good for walking, and quite comfortable.”

Johann exhales through his nose as she pops the rest of the date in her mouth, keeping her expression innocent. There’s a break in the conversation while he absorbs her story, and Petra’s mind runs like a computer, sifting through what she knows about major events that occurred after 1867 in the middle east. Johann is going to ask more questions, but she needs to figure out when she is, and where, before she gets any deeper into this relationship.

He rubs a thumb across his jaw, his beard rasping. “You’re lucky you found us, and you’re even luckier that I speak English.”

“Yes. Very lucky.” She swallows and takes another date. “Where are you from?”

“Born in Southampton to a German father and English mother, an Ellison of Southampton. I was contracted by a German Templer Colony five years ago to maintain imported machinery—milling equipment, pumps, that sort of stuff. Been here ever since.”

“I see. And where is the caravan headed, Johann?”

“Haifa,” he says, then adds, “We’ll arrive tomorrow evening, if the wheels hold.”

Haifa. The clothes, the rifles, the languages, the camels. She catalogs the details, catching them like falling drops of rain. Ottoman Haifa. She is in Palestine. Way before Israel became—becomes, she corrects her thinking—a nation in 1948. Her heart beats faster. But how much before? She can’t just ask him what year it is. The last thing she needs is to end up in an asylum.

“In Haifa… is there someone I might get help from? A place a lost woman might go for aid?” She watches him closely. Every word matters.

“Aid?” He scoffs. “There are the Ottoman officials, you’d be in worse trouble than you are already. But the Germans have a colony in Haifa, and there are some mission schools who speak and teach British English. You’ll be more likely to find a sympathetic ear there. Your uncle was digging, you said?”

“Not yet. We were still in the research phase, and there was no determined location, which makes it a lot harder to reunite with him.” She clears her throat, latching onto something that she remembers about the German Templers. “When was the Haifa colony founded?”

He waves a hand. “Decades ago. Some sixty years now, more-or-less.”

She nods, pretty sure the Templers settled in Haifa around 1870, but she needs more. She resifts through the history, grasping at events, factoids, dates, key developments in the region.

“We arrived by ship,” she says, “but I’ve heard the railways here are expanding very quickly.”

Johann nods with something like pride sparking in his eyes. “The branch just reached Haifa this year. The British and the Germans helped design some of it, of course.”

This year… but what year did the Hejaz Railway reach Haifa? Surely it was after 1900. Sultan Abdulhamid II initiated a number of reforms during the time the railway was being built—like improved transportation and communication, water sanitation, basic health services, and funding language schools.

“And the Sultan? His reforms must have made your work easier?”

Johann snorts, but like a man who is on the edge of settling into conversation with a crony. “If you call new taxes and conscription easier. But yes, it’s quieter than before.”

It’s quiet. The railway has reached Haifa, and she’s not landed during the Great War, so she’s definitely pre-1914. Nor is she after the Young Turks, a revolutionary movement inside the Ottoman Empire, staged in 1908. The region is stable, for now.

“That’s good to hear. My uncle was worried before we left, with all the talk of Russian tensions.”

“Not here. The Russians are fighting the Japanese now, father east.”

She nods, making more calculations. The Russo-Japanese war is at play. That narrows it down considerably: either in 1904 or 1905. But pieces are all she has to work with. She is in a world on the edge of a sharp collapse, but is not yet broken. The Ottoman Empire is still in place, before the Mandate, before the wars. Before the maps redraw themselves in blood and oil. Her skin flushes with gooseflesh in spite of the heat. This world doesn’t know what is coming.

Her breath slows, her pulse tightens into a steady drumbeat behind her ribs. She thinks about Alistair Graves; his grandfather found the Watcher Stele in 1903, so it has already been discovered, maybe even already shipped to Britain. Graves also claimed that the group who thought they’d discovered Enoch’s vault were lost in an earthquake in 1906. She looks away from Johann, across the rolling hills of rock and scrub. She doesn’t want him to see the excitement and turmoil now sparked inside her.

This is no coincidence.

She chose this time and place. Subconsciously, yes, but she chose it. She has landed roughly where and when she needs to be in order to continue her mission. No more dusty texts or creeping through the security systems of ancient, super-secure libraries as a sandstorm. No more Jesse, either, but that must be, for now. She will find a way back to him. She has no idea how, but she will. Right now, she is living in an era relevant to her own history, but she also faces the greatest challenge she’s ever faced. No powers. No Jesse. No money. No allies. Johann can get her to Haifa—assuming he’ll let her tag along out of pity—but after that she’ll be on her own. She has her wits and nothing else, but she is alive, breathing, and has an opportunity: not only to save a dig team from certain destruction, but—if she plays her hand perfectly—to be with them when they discover the very place that is meant to hold the Pillars of Lamech where her origin story is inscribed.

Her objective solidifies: find the dig team, use any means necessary to join them, find the pillars, take a rubbing of their markings, then get everyone away from the site before it implodes.

“What did you say your uncle’s name was?” Johann interrupts her thoughts as he takes a bite of a date.

She looks at him, and makes a split-second decision.

“Graves,” she says. “My uncle is William Graves.”

- Select your chosen format & place your order.

- Digital and audiobooks are delivered instantly via Bookfunnel. Check your email and follow the instructions to download.

- Bespoke books with special features take extra care to produce and can take 15-18 business days to ship. Watch your inbox for your tracking link.